Introducing concurrency solver

Lately at work most of the staff is puzzled with mysterious bug. In short there is a statemachine that processes movements in batches. But sometimes one particular movement is duplicated and nobody knows why...

I wish I could brag I solved it myself, but that is not the case. But it inspired me to dig a little bit in theory how distributed systems/concurrency is reasoned about and visualized.

Time space diagrams

I have read about them in some book long ago and was looking for some time find the correct name. It's pretty niche concept, but in my opinon unjustly. They are so good to visualize not only distributed systems but also concurrency.

Let me show you.

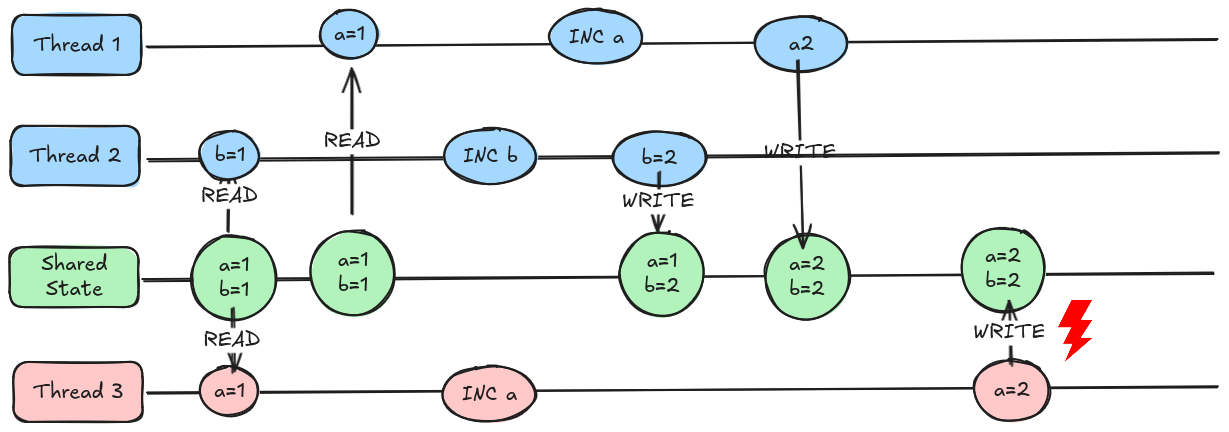

This is the basic case of dirty read, var a is not lock and therefore instead of being increamented it is wrote twice with same value 2. The example is pretty silly but you can imagine more complex scenarios where the drawing would come in handy.

Terminology

So you can imagine that the horizontal lines and crossing arrows enforce partial ordering of the events. In cases of multithreading there is no more to add but in case of distributed systems time flies different on each of the actors line.

The cut is any line cutting the diagram in half so that the partial ordering of the events is preseved. You can think of it as a snapshot or an instant in systems run. And it has associated with it a global state that corresponds to any variables on any actor alltogether.

The run is a particular combination of actions runs while preserving the partial order. So you remember that one thread can be faster in one go and in other go it can be faster than the others for instance.

If we had two threads and their actions lined up next to each other, then at each increment we would have 3 options:

- thread 1 executes, thread 2 waits

- thread 1 waits, thread 2 executes

- both execute

So all possible runs would be 3^n with n pairs of actions. This is the lattice and from it we can generate all valid runs.

Introducing Octopus

So I thought - instead of instrumenting java code and what not, why not write little modelling tool in python. And reason about the correct concurrency patters by enummerating all of the runs.

The tool that I wrote has one shared dictionary and multiple threads "processes". Processes interact with the shared state by several primitives:

- read at path

- write at path

- compute next local state on old local state

- lock at path

- unlock at path

- noop (for testing purposes)

It turns out that locking,writing and reading on XPath is really powerful and I think you can model with it any concurrency problem I know - for example Dining Philosophers.

So here it is.

To tease it up a little bit modelling looks like this:

import os, sys

sys.path.append(os.path.abspath(os.path.join(os.path.dirname(__file__), '..')))

from core import DataTransfer

from api import Octo

from config import PrintOpts

# PrintOpts.PRINT_LOCALS = False

Octo.init_shared_state({ 'a': 1})

p1 = Octo.process(name = 'Alice')

p2 = Octo.process(name = 'Bob')

def incA(locals):

locals['a'] += 1

p1.read([DataTransfer(from_path='a', to_path='a')])

p1.compute(incA, description='Increment a')

p1.write([DataTransfer(from_path='a', to_path='a')])

p2.read([DataTransfer(from_path='a', to_path='a')])

p2.compute(incA, description='Increment a')

p2.write([DataTransfer(from_path='a', to_path='a')])

Octo.solve_lattice(output='output.txt', validity_check={'a': 3})

About aforementioned problem here is solver output without locks.

And here is with locks.

I wish I also add messaging to the tool if I have more time in the future.

Conclusion

Time flies when you are having fun. If I had to reason about concurrency issues I would use such tool I just created to ennumerate all the runs and print out where the issue is.

Thanks